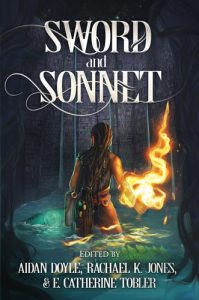

Many of the short stories I enjoyed most in 2018 came from one anthology – Sword and Sonnet, edited by Aidan Doyle, Rachael K. Jones and E. Catherine Tobler. And before I’m going to tell you about the stories I loved, I need to emphasize how awesome the anthology as a whole is. It’s about battle poets (identifying as female or non-binary), and of course this concept grabbed my attention faster than any smashing opening line. Why, yes, please let me know everything about the power of poetry, about the wielders of war-winning words, about the searing sting of a single syllable!

The diversity of these stories is absolutely fantastic, much more so than you’re probably expecting! There are tales set in forests and tales among far-flung stars, there’s revolution, revenge, and revelation, and styles range from lyrical delicacy to effective bluntness. There was not a single story in this anthology that didn’t convey its vision or failed to engage me, even if it didn’t correspond with my preferred styles or topics.

And there were a lot of stories I enjoyed tremendously: After reading about all these vastly different word slingers, I should know that there is no such thing as the quintessential battle poet. But Gennesee of A Subtle Fire Beneath the Skin by Hayley Stone somehow etched herself into my brain as just that, from the moment she sits waiting in her cell, sinister and full of hate, a victim and a perpetrator of war crimes … but still an artist. Another protagonist perceived as evil and in shackles at the beginning of her story is the witch Alejandra in El Cantar de la Reina Bruja by Victoria Sandbrook, and both stories find different and equally beautiful – but also painful – ways for seeking freedom and new beginnings through poetry.

And there were a lot of stories I enjoyed tremendously: After reading about all these vastly different word slingers, I should know that there is no such thing as the quintessential battle poet. But Gennesee of A Subtle Fire Beneath the Skin by Hayley Stone somehow etched herself into my brain as just that, from the moment she sits waiting in her cell, sinister and full of hate, a victim and a perpetrator of war crimes … but still an artist. Another protagonist perceived as evil and in shackles at the beginning of her story is the witch Alejandra in El Cantar de la Reina Bruja by Victoria Sandbrook, and both stories find different and equally beautiful – but also painful – ways for seeking freedom and new beginnings through poetry.

The Words of Our Enemies, the Words of Our Hearts by A. Merc Rustad is probably my favorite story – it’s the perfect mix of myth, bold world-building, and traces of folktale (also, dinosaurs, and trees – would have been kind of hard to pack even more things I absolutely adore into just one story). Dulce et Decorum by S. L. Huang blew my away with the questions it brought up, questions you probably have faced if you ever saw common ground between poetry and war. And This Lexicon of Bone and Feathers by Carlie St. George was exactly up my alley because it features the difficulties of translation, and was about meeting and maybe coming to understand people of wildly different cultures. It was great fun, too, as should be expected of a story about settling intergalactic conflict via art conference.

Close runners-up to these favorites were Siren by Alex Acks (the lyrical voice and the scope of this story!), And the Ghosts Sang with Her: A Tale of the Lyrist by Spencer Ellsworth (a beautiful fairytale with a charming protagonist), The Firefly Beast by Tony Pi (great atmosphere in this elegant and action-packed tale set in China), and The Bone Poet and God by Matt Dovey (featuring a bear called Ursula who is also a shaman/poet).

These were the stories that appealed most to my personal taste. As I said, I found something worthwhile and engaging in every story of this anthology, and your favorites might be different ones. Be sure to check them out!